Later this year, environmentalists around the world will celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Storm King decision. The official tale is well-rehearsed: courageous locals rose up to stop a corporate behemoth from defacing Storm King Mountain with a monstrous hydroelectric plant.

But what if that story is more of a myth than a memory?

What if the project would have been nearly invisible, tucked beneath the mountain while leaving it intact?

What if the host community of people, who actually lived in Cornwall, overwhelmingly supported it?

What if organized labor backed it, prominent politicians endorsed it, and the plan promised not destruction, but revival: clean power, jobs, and desperately needed investment in a declining region?

What if Storm King wasn’t stopped because it was evil, but because it was too good?

And how many preventable deaths and hospitalization occurred in New York City because it wasn’t built?

Storm King marked a turning point in American history, where a powerful alliance of elite families, foundations, and ideological operatives learned how to kill a future they couldn’t control. It was the moment when the postwar dream of progress and development gave way to something darker.

Sign up for New York Energy Alliance’s mailing list here.

The Case for the Storm King Plant

In the 1960s, New York City was at a breaking point. Electricity use had more than doubled since the end of World War Two, and office towers filled with lights, elevators and early computers were being built at a dizzying pace.

Brownouts and blackouts were becoming increasingly common in Manhattan and the Bronx, especially during the hottest days of the year when demand would spike. Consolidated Edison, the local utility company, relied on an aging patchwork of oil and coal-fired plants that were located within city limits. These plants were largely the source of massive amounts of air pollution in the city.

In particular, Con Ed’s Astoria Energy Complex, consisting of the “Big Allis” Ravenswood peaker plant, the Astoria Generating Station, and the Charles Poletti Power Plant, was the nucleus of what is now known as “Asthma Alley,” where there are disproportionate health impacts from air pollution to this day.

These two factors meant that Con Ed was desperate for reliable and clean sources of energy that were close enough to the city’s grid to help shoulder the load. The addition of Indian Point 1 in 1962 helped, but electricity demand kept increasing at a rate of 7% a year.

That’s when the Storm King hydropower plant, 60 miles north of New York City on the Hudson River, was proposed. A 2,000 megawatt pumped-storage facility, it would have been among the largest in the world and added more than 25% to Con Ed’s capacity.

“The Cornwall plant would do much to cut down the amount of air pollution in New York City… it would enable us to reduce the amount of coal and oil burned in New York and to shut down several hundred thousand kilowatts of our older steam electric generating units.”

M.L Waring, senior vice-president of Con Ed

A Plan With Many Supporters

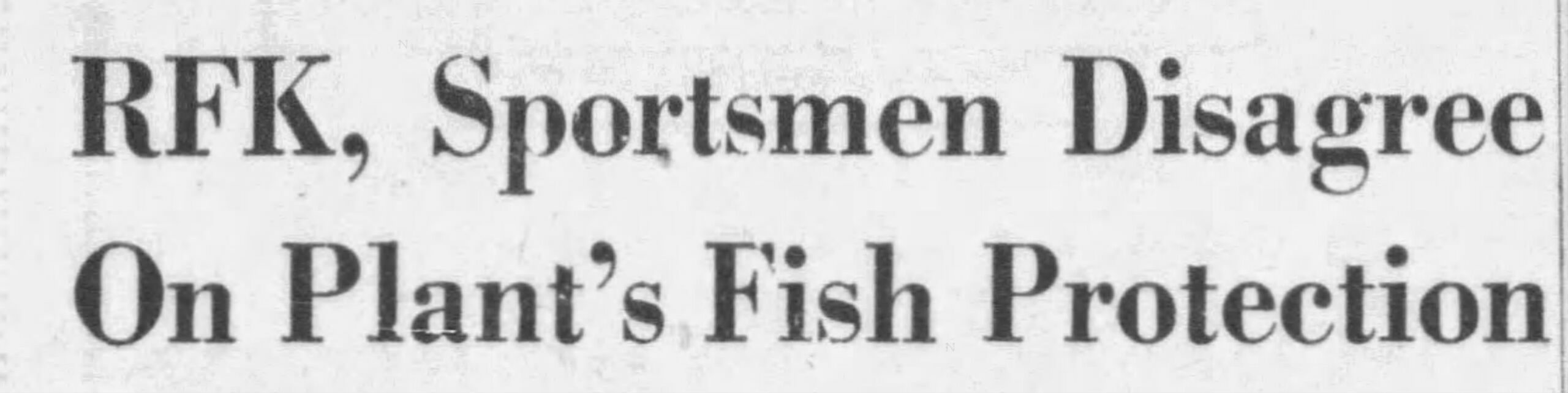

The Storm King project was very popular in its host community of Cornwall and the nearby city of Newburgh. Village and Town citizens, officials and labor leaders were vastly in favor of the project for the benefits it would provide: economically, environmentally and in funding infrastructure improvements for their community.

The biggest booster of the plant was the Village of Cornwall’s mayor, Michael Donahue.

Con Edison will pay annual taxes of $500,000, and with these increased revenues we shall be able to construct a new village hall, library, village garage, parks, a recreational center, nature trails, and municipal ski slopes.

Village of Cornwall Mayor Michael Donahue, 1964

Cornwall’s tax assessor, Wesley Rowland, estimated that the $400 million facility would contribute approximately $100 million to the town’s existing $132 million tax base. It was an enormous boost for a community of only 10,000 residents.

In nearby Newburgh, the struggling city had just gone through a vicious multi-year welfare crisis. A $165M industrial development project just five miles away was needed to “bolster its depressed economy, to provide employment, and to add stimulus to the rebirth of Newburgh.”

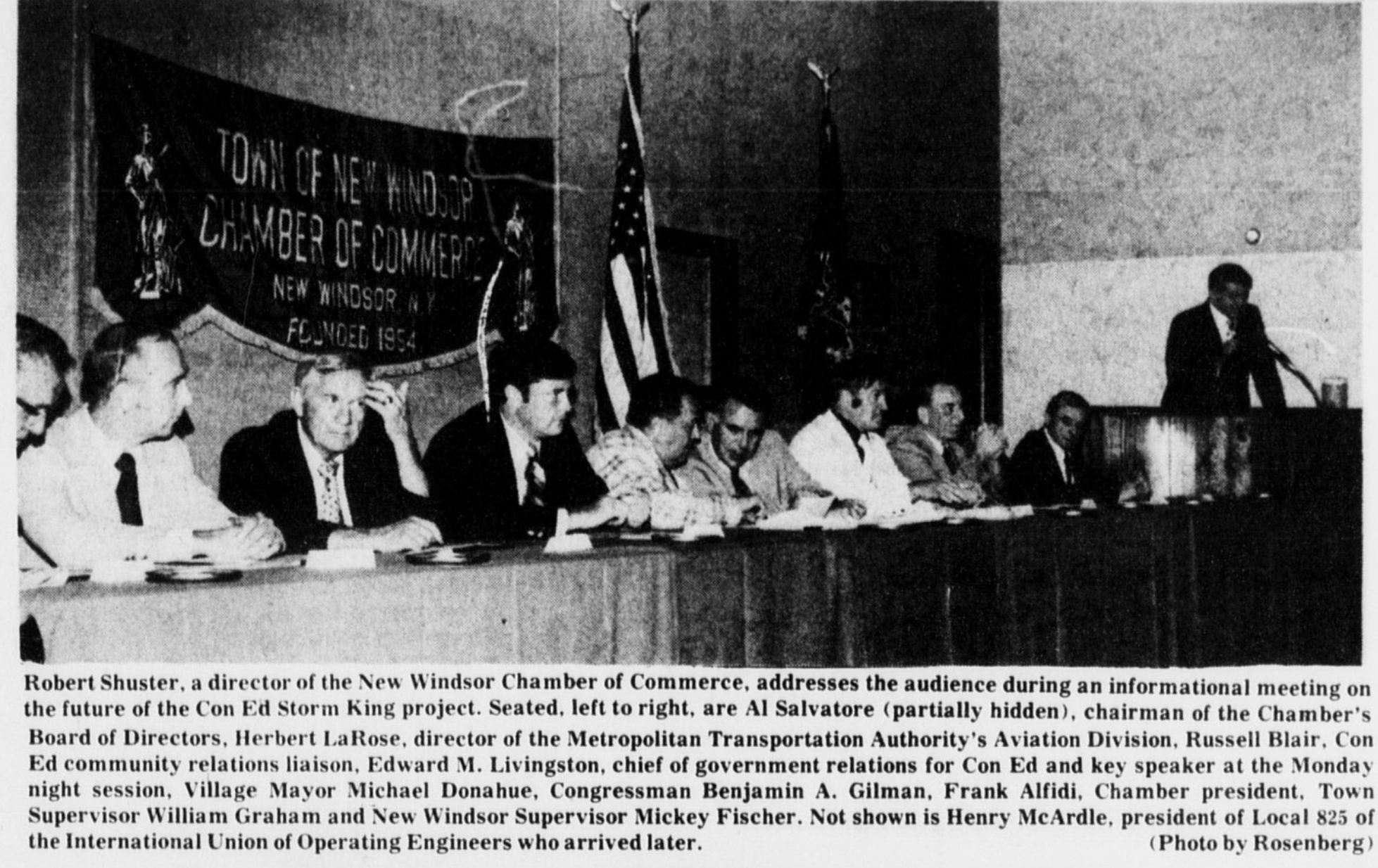

Organized labor also stood firmly behind the Storm King project, viewing it as a rare chance to bring long-term, well-paid employment to a region suffering from chronic underdevelopment. Construction unions, engineers, and utility workers all testified in support of the hydroelectric plant, emphasizing jobs, economic stimulus, and the project’s environmental compatibility.

Henry P. McArdle, business representative of Local 825 of the Operating Engineers Union, said the plant would offer years of steady employment.

“This would [be] long-term employment for these men,” he said. “There are few jobs for men in the area.”

Con Edison also offered to clean up the waterfront in Cornwall, which was littered with industrial waste. The Cornwall Local reported that 1,700 people signed a petition in support, with only 100 opposed.

The Opposition: From Aesthetics to Fish

Initial designs for the facility had transmission lines running across the Hudson River and a small but noticeable intake area on the waterfront. In an early flyer about the plant, Consolidated Edison zoomed in on the design rendering to show detail, which gave the false impression that the project was going to swallow the mountain whole.

“An artist’s rendering… showed the side of the Mountain cut away, leaving a gash… It was this illustration, in particular, that roused lovers of the Highlands to action.”

Albert Butzel, 2014

New renderings were quickly created, but it was too late. The original is the one that was plastered everywhere.

A group of “old money” Hudson River families saw the project as a threat to their legacy of conservation efforts in the region. Several of them were clustered across the river and to the south in Garrison, NY.

“From a very early point, diehard opponents of Con Ed’s plans would refuse to see the project in isolation; instead, they would come to view it as a harbinger of the industrialization of the Hudson River valley. Perhaps more importantly, many environmentalists, feeling overwhelmed at the changes they had witnessed during their lives, developed a militant, winner-take-all attitude when it came to land-use struggles.

Carl Carmer [took]… a definitive stand: ‘It is my conviction that those who would destroy the beauty of our landscape should be fought off, not appeased. Appeasement is a postponement and if we are to preserve the landscape of the America we have come to love, postponement is the equivalent of complete surrender.’”

Robert Lifset, Power On the Hudson, 2014

Alexander Saunders was one of the leaders of the opposition to the plant. From his estate in Garrison, he said “we don’t feel this is the right area for industry. Of course, there are a lot of people on the welfare rolls in Newburgh, but as a businessman, I can tell you it doesn’t represent a very high calibre for a work force… the ideal land use for this area should be for recreation for people from New York City.”

Saunders was the chairman of the Scenic Hudson Preservation Conference and the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater organization started with a party at his house.

For these new preservationists, the Storm King battle was not about securing improvements or concessions; it was about fighting an indefinite war against industrial society in all its forms. Once it was clear that the plant would be virtually invisible on the Hudson River and an aesthetic argument would be impossible, the activists seized upon the idea of fish and fishermen being affected by the plant.

This strategic pivot was led by Bob Boyle, the future mentor to Robert F. Kennedy Jr., in his sensational 1965 Sports Illustrated article, “A Stink of Dead Stripers.” Writing with a hysterical verve, Boyle abandoned the dry legal terrain of viewshed arguments and plunged instead into a lurid story of ecological doom, spinning a pile of decomposing fish near the Indian Point nuclear plant into a casus belli for total war over Storm King.

“Perhaps, ironically, the Hudson River, the living river, may yet be saved by dead fish long thought buried in an obscure dump.”

Robert Boyle

After publishing the article, Boyle met with two Scenic Hudson leaders, and congratulated them for their ongoing legal case against the plant.

“He wanted them to know that the Hudson River in the vicinity of the Storm King plant was one of two principal spawning grounds for America’s Atlantic Coast striped bass population… “The striped bass spawn here,” Boyle said, “and it’s a very important area for larvae and plankton, and the pump storage plant will suck up the eggs and young.” [Scenic Hudson co-founder] Duggan recognized that this was the issue that could win the case. She rose with a gleeful smile and proclaimed, “They’re going to kill the fish! They’re going to kill the fish!” She was so excited, recalls Boyle, “It was like Churchill hearing Pearl Harbor had been bombed.”

John Cronin, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., The Riverkeepers, 1999

This strategic pivot was also noted by Con Ed:

“[The opponents are] still not satisfied; they now purport to espouse seriously a whole series of objections based on what will surely be shown here to be insupportable, far-fetched and exaggerated theories of disaster to flora, fauna, dikes and water supplies. One opposing witness has even taken the desperately extreme position that the plant should not now be built underground and invisible, the witness will know it’s there.”

James O’Malley, Con Ed Chief Counsel, 1966

This extremism was even noted by New York Senator Robert F. Kennedy, who testified to Congress that he “cannot believe that our marine biologists are unable to offer assistance in meeting this problem on the Hudson. I cannot believe that a solution to the problems with the Storm King project…. cannot be found.”

He also noted that Con Ed had offered to build a screen shielding the intake pumps at Storm King, and believed a solution could be found to the fish life questions.

Alfred Perlmutter, a professor of biology at New York University said that “one active sport fisherman would have as much effect on striped bass egg larvae” as the project would.

It was the romanticism of fish and fishermen on the Hudson River that stretched out an open-and-shut case over aesthetics into something that could go on indefinitely. Environmental non-profits spawned like fish in the Hudson; the old guard of the Hudson River Conservation Society led to Scenic Hudson, which led to the Rockefeller-supported Clearwater, the Ford Foundation-supported National Resources Defense Council, the Rockefeller/Harriman-led Hudson River Valley Commission, and the Hudson River Fisherman’s Association, which soon morphed into the Robert F. Kennedy Jr.-led Riverkeeper group.

The Death of Storm King

Storm King was a David & Goliath fight, but it’s quite possible that Con Ed was David and the old money hydra it faced was Goliath. By the 1970s, changes to the U.S. monetary system and interest rates meant that what was once a $150M plant was slowly turning into a $1B project, where the economics could never pencil out despite an ongoing energy crisis and multiple blackouts in New York City.

The financing was made even more difficult because the national response to the energy crises of 1970s was, as Jimmy Carter put it, to put on a sweater and turn the heat down. Con Ed could not rely on steady growth in electric demand to pay for the plant. Additionally, the plant became leverage for Con Ed in negotiations with environmentalists over building cooling towers at Indian Point nuclear plant.

The Village of Cornwall’s Mayor Donahue never stopped advocating for the plant. “They’ve had conservationists all the way from Australia talking about Storm King,” he said in 1973. “They never want to know what the local people think.”

In 1976, he continued: “We – the project supporters – contend that the Cornwall plant is in the public interest. We firmly believe that it would contribute substantially to the economy of this community, that it would enhance the preservation of scenic beauty and that it would enhance the preservation of scenic beauty and that it would not affect conservation of the river’s fishery.”

According to a Con Ed official, the construction of the plant would have supported a $35M annual payroll and employed 1,500 Orange County employees from eight county labor unions.

A union workman, reacting to one of the endless delays in the project, was blunt:

“We are all bitter as hell. This whole controversy has been ginned up by outsiders. Why should I lose my job because some guy may not be able to catch his limit of striped bass off his pleasure boat?”

But after years of lawfare, the plant was killed in closed door negotiations in 1980 between Con Ed and 10 other organizations, mediated by Russell Train, former head of the EPA and Malthusian head of the World Wildlife Fund.

A Final “What If”

Today, the proposed alternative to the “Asthma Alley” power plants in New York City is to locate dangerous lithium-ion battery plants right inside major population centers, with a mandate to build six gigwatts of battery storage statewide by 2030. The peaker plants are still running.

The cognitive dissonance over energy and the environment that resulted from the Storm King case is almost too much to take in. The added air pollution, asthma hospitalizations, increased energy costs, and now, the desperate crunch for clean energy storage in New York State makes seeing the sordid affair as an “environmental” landmark utterly absurd.

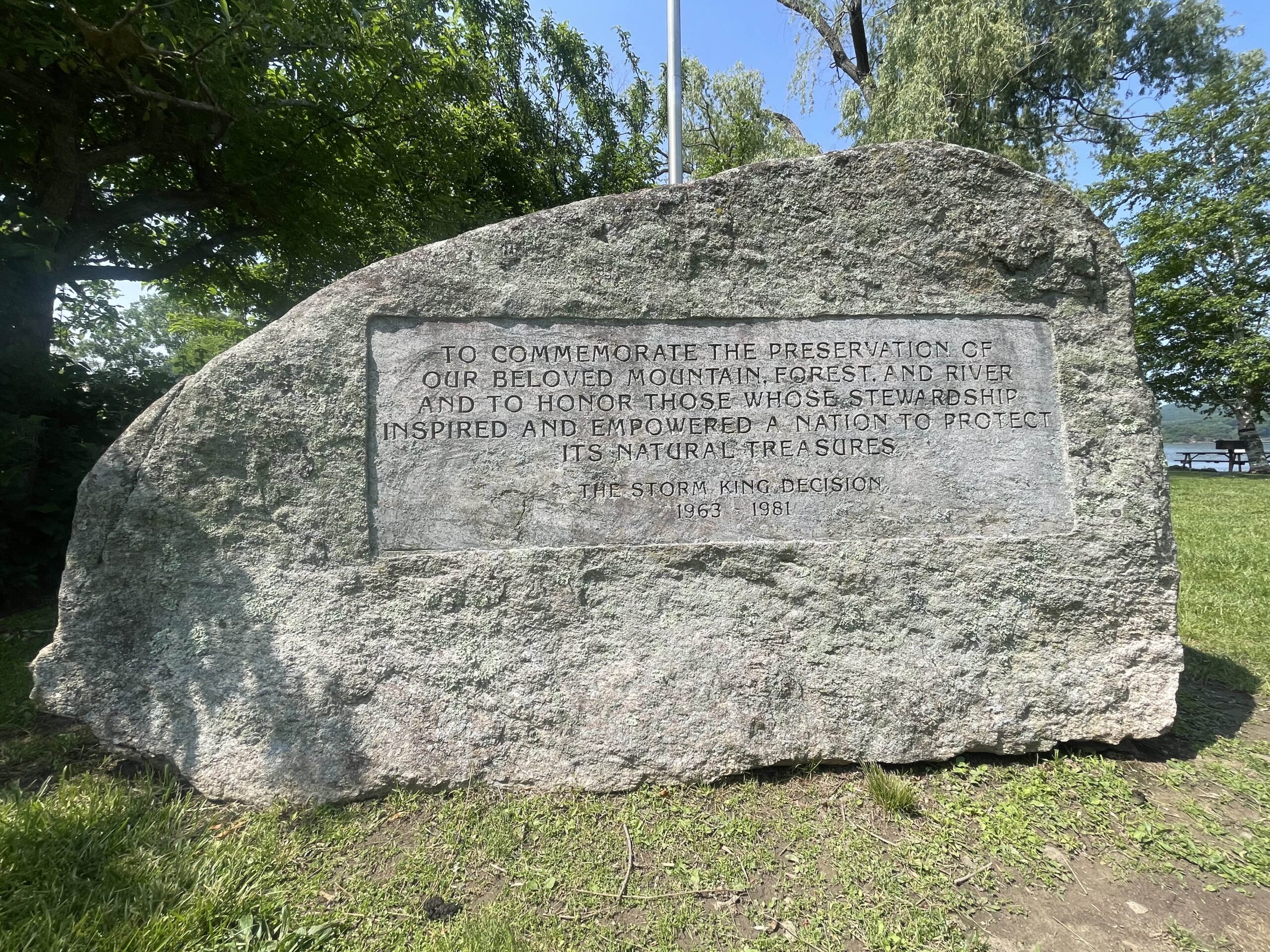

As for the good Mayor Donahue, he served as Cornwall’s beloved mayor for 28 uninterrupted years ending in the late 1970s. The lost promise of the Storm King plant was the great “what if” of his tenure, forever beyond his grasp. After the settlement, Con Ed donated land to the Village of Cornwall which was later dedicated as Donahue Memorial Park, in his memory. Approaching the park, you might only notice one plaque:

If you move to the left, buried behind foliage, you’ll find a second plaque dedicated to the memory of Mayor Donahue. You can see the faded tribute to him below, with Storm King Mountain in the background to the right:

In 2009, the more prominent plaque was added with much controversy. The addition was protested by Donahue’s surviving daughters, as it commemorated the elite environmentalists that Donahue fought against for 15 years.

The plaque faces outward toward Storm King Mountain, gleaming and well-maintained. Behind it, Donahue’s original plaque is nearly hidden—faded, weather-stained, and shrouded by overgrown foliage, like the memory of the future he once fought for. It maybe be obscured—purposefully hidden from the light of day—but Donahue’s plaque still stands, like the truth, waiting to be rediscovered.